Ten Mistakes to Avoid in the Construction of Single-Layer Armour Units Using Artificial Concrete Blocks

Single-layer armour systems using artificial concrete blocks are based on a fundamental principle:

their stability relies on the interlocking of the units and does not tolerate any significant defect.

International best-practice guidelines, in particular the CEREMA Rock Armour Guide (French translation of the Rock Manual), emphasize that these structures are designed for zero damage.

They clearly state that even damage levels below 5% are not acceptable, due to the limited residual strength of single-layer armour systems and the potentially progressive nature of resulting failures.

In practice, however, experience shows that numerous non-conformities appear as early as the construction phase: interlocking defects, placement errors, insufficient quality control, or misinterpretation of digital guidance and inspection tools.

Drawing on more than twenty years of intervention on international construction sites, CLAS has identified a limited number of recurring errors, common to all single-layer artificial concrete armour units, regardless of the technology used.

When these errors are not detected and corrected immediately, they may develop into major defects, compromise the stability of the armour layer, and durably affect the long-term performance of the structure.

To learn more, click on a link below:

Risk Assessments for Single-Layer Armour Systems

Breakwater Expertise and Assessment

Training for Placement Teams & Safety

References

Mistake No. 1 — Confusing Theoretical Positioning with Actual Interlocking of the Units

The fundamental principle that must never be overlooked

In a single-layer armour system using artificial concrete blocks, stability is not ensured by the theoretical position of the units, but by their actual interlocking, block by block, with the units in the lower row and the supports provided by the underlayer.

A unit may be perfectly positioned relative to a theoretical target (coordinates, placement drawings, profile envelope) while still being poorly interlocked.

This confusion is one of the most frequent causes of non-conformities observed in single-layer armour breakwaters.

Frequent origin of this error

This error generally occurs when:

placement is primarily guided by theoretical positioning tools (GPS, POSIBLOC™);

the underlayer presents asperities or irregularities that are not detected;

the unit remains caught on an element of the underlayer and does not reach its final interlocking position;

placement teams do not have sufficient training to read and assess actual interlocking;

placement control is too infrequent or insufficient.

Experience shows that a significant proportion (30% to 50%) of units placed “naturally” on their target do not spontaneously reach their optimal interlocking position.

Associated risks

A poorly interlocked unit retains a residual freedom of movement.

Under the effect of its own weight, hydraulic loading, or the first storm events, it may:

slightly settle or tilt;

lose its initial supports;

cause impacts with adjacent units;

lead to concrete breakage;

initiate a progressive unraveling of the armour layer.

A single poorly interlocked unit may be sufficient to trigger a local defect, which may then evolve in a progressive and often irreversible manner.

Why theoretical tools are not sufficient

Placement drawings, numerical models and guidance tools are placement aids, but do not guarantee actual interlocking:

they represent an ideal geometry, not the reality of contact between units;

they do not always allow proper assessment of support quality;

they do not detect micro-residual movements;

they may conceal defects related to the underlayer.

Only direct visual inspection, both above and below water, makes it possible to confirm that the unit is truly locked in place, with no possibility of subsequent movement.

Recommended corrective action

When an interlocking defect is identified:

the affected unit must be adjusted immediately, while repositioning means are still available;

if the cause is related to an underlayer defect, it must be corrected before any new placement;

in some cases, localized rework is possible without complete dismantling of the area, provided that specific know-how and real-time control are available.

Delaying the correction of an interlocking defect almost always leads to an increase in the volume and cost of subsequent remedial works.

Key takeaway

👉 In a single-layer armour system, complying with the target position is not sufficient.

What matters is the actual, stable and final interlocking of each individual unit.

Mistake No. 2 — Tolerating Out-of-Profile Units in a Single-Layer Armour System

What “out of profile” really means

A unit is considered out of profile when it lies outside the geometric envelope defined by the breakwater profile (slope, crest or toe), even if it appears stable in the short term.

In a highly interlocking single-layer armour system, compliance with the profile is not an aesthetic or secondary criterion:

it directly governs hydraulic stability, load distribution and the proper functioning of the interlocking mechanism.

Common causes of out-of-profile units

Out-of-profile situations most often occur when:

the underlayer shows planarity or thickness defects;

placement is carried out without accurate visual control of the final envelope;

priority is given to production rate rather than placement quality;

placement teams do not immediately perceive the critical nature of the deviation;

inspections are spaced too far apart or carried out too late.

A unit may therefore appear to be correctly placed when considered individually, while still creating a geometric discontinuity within the armour layer.

Associated risks

An out-of-profile unit presents several major risks:

increased exposure to wave action, particularly in the crest zone or near the surface;

potential extraction during a significant energetic event;

falling of the unit, causing impacts on the underlying units;

creation of a localized void, promoting the extraction of neighboring units;

initiation of a progressive unraveling of the armour layer.

In a single-layer armour system, the extraction of a single out-of-profile unit may be sufficient to trigger an extensive failure.

Why an out-of-profile unit must never be tolerated

Unlike certain double-layer structures, single-layer armour systems have a low reserve of resistance.

They are designed for zero damage, and any geometric deviation significantly increases local vulnerability.

An out-of-profile unit is not an isolated defect:

it alters the bearing conditions, interlocking mechanism and load transfer throughout the adjacent area.

Recommended corrective action

When an out-of-profile unit is identified:

the affected area must be treated immediately;

the unit must be repositioned to reintegrate the design profile envelope;

if the cause is related to a sub-layer defect, it must be corrected before any reinstallation;

in some cases, a localized repair is possible without full dismantling, provided that appropriate expertise is available.

Waiting until the structure is put into service to address an out-of-profile unit almost always leads to heavier, more costly and riskier interventions.

Key takeaway

👉 An out-of-profile unit is a structural weak point.

In a single-layer armour system, it must be corrected without delay.

Error No. 4 — Treating all broken units in the same way

A broken unit is not automatically a critical defect

In a single-layer armour made of artificial concrete units, the presence of a broken unit does not systematically lead to a serious disorder.

The mistake lies in applying a single, uniform rule, without analysing the real context in which the breakage occurred.

A broken unit must always be analysed, but it does not necessarily have to be replaced.

Key parameters in the analysis of a broken unit

The risk assessment associated with a broken unit is based on several essential criteria:

the position of the unit within the armour layer (toe, mid-slope, upper zone);

its role in the local interlocking;

the quality of its supports on the underlayer and on adjacent units;

the blocking provided by the upper rows;

the isolated or repetitive nature of the breakage.

These elements directly determine the actual level of risk to the stability of the structure.

Example of a broken unit with no impact on stability

A broken unit located:

at the toe of the breakwater,

properly wedged by the toe rockfill,

blocked by the units of the upper row,

showing no residual freedom of movement,

can be left in place without risk to the stability of the armour layer.

In this specific case, the risk level is zero, and any intervention would be unnecessary, or even counterproductive

Example of a broken armour unit with high risk

Conversely, a broken armour unit located:

in the middle of the armour layer,

directly contributing to interlocking,

showing a loss of mechanical interlock with adjacent units,

may lead to:

a local loss of interlocking,

residual movements under wave action,

a propagation of forces,

and, in the long term, a progressive unraveling of the armour layer.

In this case, the risk is not related to the breakage itself, but to the loss of the mechanical function of the unit within the interlocking matrix.

L’importance de rechercher la cause de la casse

Avant toute décision, il est indispensable d’identifier l’origine de la casse :

choc lors de la pose ou d’un ajustement tardif,

mauvaise imbrication initiale,

appui instable sur la sous-couche,

point dur entre blocs,

mouvements répétés sous houle.

Cette analyse permet de déterminer si la casse est :

isolée,

ou le symptôme d’un défaut plus global de mise en œuvre.

Why the number of broken blocks is a key indicator

An isolated break does not reflect the same situation as multiple or repeated breaks within the same area.

An isolated break, when properly analysed, may be tolerated.

Multiple breaks, on the other hand, are often a sign of:

a generalised interlocking defect, or

a design or construction issue.

In this second case, the affected area must be considered potentially unstable.

Key principle to remember

👉 A broken block is neither acceptable by principle, nor condemnable by principle.

It must be subject to a risk analysis based on its position, its role in the interlocking system, the cause of the break, and whether it is isolated or not.

It is precisely this differentiated approach, based on real observation and field experience, that makes it possible to avoid both:

unnecessary repairs,

and dangerous underestimations.

Error No. 5 — Using the wrong criterion: the size of openings is not the risk, the extraction of the underlayer is

In a single-layer armour made of artificial concrete units, the presence of voids or openings between units is inevitable and forms part of the normal functioning of the structure.

The mistake is to assess whether a void is acceptable or not solely on the basis of its apparent size, without analysing its actual effect on the stability of the underlayer.

There is no universal “maximum acceptable hole size”.

The determining criterion is another one:

👉 Does the void allow, or not, the extraction of the blocks or materials forming the underlayer under wave action?

Frequent origin of the error

This confusion most often arises from:

a superficial visual interpretation of the armour layer,

analyses based solely on images (drone, sonar, digital models),

or an excessive desire to simplify during conformity checks.

A visually impressive opening may be entirely harmless, whereas a more discreet aeration can become a starting point for progressive unraveling if it allows mobilisation of the underlayer.

Actual risk associated with aerations

The risk is not related to the opening itself, but to what it makes possible:

progressive extraction of underlayer stones or materials,

loss of support of adjacent armour units,

differential movements,

block breakage,

followed by progressive unraveling of the armour layer.

Once the underlayer is degraded, the overall stability of the single-layer armour is rapidly compromised.

Correct analysis principle

Any aeration observed in a single-layer armour must be analysed taking into account:

the grading and nature of the underlayer,

the position of the aeration (toe, mid-slope, near the surface),

the local hydraulic exposure,

the actual ability of wave action to mobilise the underlayer through this opening.

Only after this analysis can the aeration be classified as:

harmless,

to be monitored,

or requiring immediate corrective action.

CLAS position

CLAS never reasons in terms of a “acceptable hole” or “unacceptable hole” based solely on a measured dimension.

The analysis is based exclusively on the real risk of underlayer extraction and on the physical mechanisms observed on real structures.

This approach makes it possible to avoid both:

unnecessary repairs,

and the dangerous underestimation of genuinely critical defects.

Error No. 6 — Underestimating the critical role of the underlayer in the stability of the armour layer

The underlayer forms the mechanical interface between the structure and the armour layer made of artificial concrete units.

Its role is not limited to providing a geometric support: it directly governs the quality of interlocking, the long-term stability of the units, and the ability of the armour layer to dissipate wave forces.

Underlayer outside tolerances: a direct cause of non-conformities

An underlayer that does not comply with the prescribed geometric tolerances (profile, slope, regularity) immediately generates placement defects, including:

out-of-profile armour units,

inadequate support on the lower row,

incomplete or blocked interlocking in the upper zones,

repeated difficulties in adjusting units during placement.

Under such conditions, artificial armour units may appear correctly positioned at the time of installation, while still retaining a residual capacity for movement that may later be activated under wave action.

Geometrically compliant underlayer… but mechanically unsuitable

Even when geometric tolerances are respected, an underlayer constructed with overly rounded or rolled rock (pebbles) can represent a major risk factor.

This type of gradation promotes:

micro-displacements of armour units,

progressive loss of bearing support,

delayed adjustments after placement,

including for units that were initially strongly interlocked.

Field experience shows that apparent stability at the end of placement does not guarantee long-term stability if the underlayer does not exhibit appropriate mechanical behaviour.

Limitations of multibeam sonar surveys for underlayer control

Multibeam sonar surveys are frequently used to control the geometry of the underlayer. However, they present fundamental limitations:

they only reproduce the external envelope of the underlayer,

they do not allow assessment of the actual thickness of the layer,

they provide no reliable information on gradation or bearing conditions,

their results may be influenced by acquisition and processing parameters.

As a result, sonar surveys may give the illusion of a compliant underlayer, while the real mechanical conditions are unfavourable to proper interlocking.

Final inspection essential before armour unit placement

Regardless of the quality of preliminary controls, a complete visual inspection of the placement surface is an essential step immediately before installing the armour units.

This inspection, carried out as close as possible to real site conditions, allows:

verification of the actual regularity of the underlayer,

identification of hard points, asperities or unstable zones,

anticipation of placement and interlocking difficulties,

avoidance of defects that can no longer be corrected once the armour layer is in place.

👉 A single-layer armour does not compensate for an unsuitable underlayer.

The quality of the underlayer directly governs the quality, stability and durability of the structure.

Erreur n°7 — Remplacer l’observation réelle par des outils numériques ou acoustiques

The evolution of digital and acoustic tools has profoundly changed the monitoring methods used on maritime construction sites.

3D models, GPS positioning, acoustic cameras, multibeam sonars and real-time imaging systems are now widely used to assist the placement and inspection of single-layer armour systems.

The mistake lies in assigning them a role they cannot fulfil on their own.

Support tools, not validation tools

These technologies were developed to:

improve safety,

speed up certain operations,

provide an overall representation of the structure.

However, they do not allow validation of the actual interlocking, nor do they allow reliable assessment of:

the quality of block-to-block supports,

the effective contacts with the underlayer,

micro-movements,

the early onset of mechanical disorders.

An armour layer may appear “compliant” on a screen while, in reality, it presents critical defects that are invisible in digital data.

A representation that may diverge from reality

Field experience shows that digital tools may:

display contacts that do not exist,

indicate holes or defects that are not real (artefacts),

mask actual non-conformities,

produce measurement deviations incompatible with the tolerances required for proper block interlocking.

These limitations are amplified by:

wave action,

water turbidity,

the presence of air,

the complex geometry of artificial armour units,

which disturb the propagation and interpretation of acoustic signals.

The false sense of security of “all-digital” approaches

Relying exclusively on digital or acoustic tools leads to an illusion of control:

decisions are taken remotely,

analysis is based on reconstructed images,

understanding of the real stability mechanisms is weakened.

Yet, in a single-layer armour, stability is governed by a few centimetres — sometimes by just a few contacts — which cannot be properly assessed without direct observation.

Human observation remains irreplaceable

Only real-world observation, carried out by experienced inspectors and professional divers, makes it possible to:

see and physically touch the blocks,

assess supports and mechanical locking,

detect residual movements,

identify defects before they become irreversible.

Digital tools must remain complements, never substitutes, for direct inspection.

👉 In single-layer armour systems, what is not seen on the structure is not under control.

Error No. 8 — Underestimating the training of installation teams

The construction of a single-layer armour using highly interlocking artificial concrete units is not a matter of simple handling skills.

It is a specialised profession, combining an understanding of the mechanical behaviour of the armour layer, mastery of placement rules, and the ability to analyse, in real time, the situations encountered on the slope.

The frequent mistake is to assume that:

reading technical documentation,

a short theoretical training course,

or general experience in maritime works,

are sufficient to guarantee compliant installation.

Single-layer placement cannot be improvised

A stable single-layer armour relies on:

precise bearing conditions,

real and fully locked interlocking,

the absence of residual block movement,

and continuous adaptation to local conditions (underlayer, tolerances, wave action, visibility).

These parameters cannot be assimilated instantly.

They require progressive learning, based on repetition, observation, and immediate correction of errors.

Training ≠ information

Effective training is not limited to:

explaining the block geometry,

showing mesh diagrams,

or commenting on a placement plan.

It must include:

practical training on the actual structure,

learning how to “read” the armour layer,

understanding failure mechanisms,

and the ability to immediately recognise improper interlocking.

In single-layer armours, what is not understood at the time of placement becomes a disorder later.

The illusion of rapid ramp-up in production rate

Another common mistake is to seek a high production rate from the very start of the project, without allowing teams the time to acquire the correct reflexes.

This approach generally leads to:

an accumulation of defects that are invisible in the short term,

late and costly dismantling operations,

a sudden drop in production during corrective phases,

and a loss of confidence between the project stakeholders.

Experience shows that a progressive ramp-up in production, supervised by close and continuous controls, on the contrary makes it possible to:

achieve high and sustainable production rates,

with controlled quality,

and without major rework.

Safety training is an integral part of quality

The placement and inspection of single-layer armours often involve:

professional divers,

heavy handling operations,

degraded visibility conditions,

and direct-contact interventions on the blocks.

Insufficient training in safety specific to single-layer armours:

limits inspection capabilities,

reduces the quality of adjustments,

and sometimes leads to abandoning inspections that are nevertheless essential.

Safety directly conditions placement quality.

A rare skill, built over time

Effective training of placement teams is not acquired in a few days, nor through document transfer.

It relies on:

experienced supervision,

a continuous on-site presence,

and accumulated feedback from numerous projects.

It is precisely this combination of training, experience and control that makes it possible to achieve a stable, durable single-layer armour compliant with best practice.

Error No. 9 — Carrying out inspections too late or at the wrong time

In the construction of a single-layer armour using artificial concrete units, the timing of inspections is just as important as the inspection itself.

A frequent mistake is to assume that non-conformities can be detected and corrected a posteriori, once several rows have been placed, or even at the end of the construction phase.

This approach is incompatible with the actual behaviour and functioning of single-layer armour systems.

The right time to inspect: before decisions become irreversible

Most critical defects — poor interlocking, insufficient supports, out-of-profile units, unfavourable interaction with the underlayer — can only be effectively corrected while the armour units remain accessible.

When several upper rows have already been placed:

adjustments become impossible,

corrections require heavy dismantling,

and the technical, economic and contractual costs escalate.

Late inspection turns minor defects, which could have been corrected in real time, into major disorders requiring extensive remedial works.

Inspection frequency: a determining factor

Another common pitfall is spacing inspections too far apart in an attempt to maximise placement rates.

In single-layer armour systems, this approach is counter-productive:

the more inspections are spaced out,

the greater the number of potentially non-compliant units,

and the more complex and penalising remedial works become.

Experience shows that frequent, targeted and close-interval inspections:

drastically reduce dismantling,

allow immediate adjustments,

and ultimately improve overall site productivity.

The pitfall of “a posteriori” inspections

Inspections carried out solely:

by sonar surveys,

by digital reconstructions,

or by partial visual inspections above water,

do not allow the identification of all critical defects.

These tools can be useful, but they do not replace direct observation of the actual interlocking, in particular:

the quality of the supports,

residual freedom of movement,

and the interaction with the underlayer.

An inspection carried out too late, even if technologically sophisticated, no longer makes it possible to guarantee the real stability of the armour layer.

Inspection as a tool for site management

In a controlled approach, inspection is neither a sanction nor an administrative formality.

It is an operational site-management tool, making it possible to:

guide placement progressively as works advance,

adjust the installation rate to real site conditions,

and secure each critical stage of construction.

This approach requires:

inspections carried out both at the surface and underwater,

performed at a time when corrections are still simple,

and fully integrated into the placement process, not dissociated from it.

Quality and productivity are not opposed

Contrary to a common belief, increasing the frequency of inspections does not undermine quality or productivity.

On the contrary, it makes it possible to:

avoid large-scale dismantling operations,

stabilise the installation rate over time,

and secure contractual deadlines.

In single-layer armour breakwaters, a late inspection always costs more than a frequent, well-anticipated one.

Error No. 10 — Confusing documentary compliance with the actual structural stability of the structure

One of the most widespread mistakes in single-layer armour breakwater projects is to assume that a structure is compliant simply because the documentation is compliant.

Approved drawings, satisfactory digital surveys, consistent control tool reports, certificates delivered:

all of this can create the illusion of overall compliance.

However, the actual stability of a single-layer armour layer cannot be demonstrated on paper.

Documentary compliance does not guarantee real interlocking

The stability of single-layer armour layers relies on:

the effective interlocking of the armour units,

the quality of their supports on the underlayer,

and the correct transmission of forces between units.

No document, no numerical model, and no indirect tool can, on its own, verify:

the absence of residual freedom of movement,

the reality of the contacts between units,

or the local mechanical behaviour of the armour layer.

A structure may be perfectly compliant from a documentary standpoint and yet still present critical invisible defects, likely to evolve under wave action.

Le piège des validations tardives

Lorsque la conformité est évaluée uniquement :

en fin de phase travaux,

ou sur la base de contrôles indirects a posteriori,

les décisions deviennent binaires : accepter ou reconstruire.

Or, la majorité des non-conformités observées sur les carapaces monocouches :

sont corrigeables simplement lorsqu’elles sont détectées tôt,

deviennent complexes, coûteuses et conflictuelles lorsqu’elles sont découvertes trop tard.

La stabilité d’une carapace monocouche ne se valide pas une fois l’ouvrage achevé,

elle se construit et se sécurise bloc par bloc, au moment de la pose.

The pitfall of late validations

When compliance is assessed only:

at the end of the construction phase,

or on the basis of indirect, a posteriori inspections,

decisions become binary: accept or rebuild.

However, most non-conformities observed in single-layer armour layers:

can be corrected easily when detected early,

become complex, costly and conflict-prone when discovered too late.

The stability of a single-layer armour layer is not validated once the structure is completed;

it is built and secured block by block, at the time of placement.

Real stability vs theoretical compliance

International best practice rules are clear:

single-layer armour layers are designed for zero damage.

This requirement does not mean:

that no deviation can exist at any given moment,

but that any deviation must be analysed, classified and treated according to its real impact on the stability of the structure.

It is precisely to bridge the gap between:

theoretical compliance,

and real stability,

that an approach based on:

direct observation,

analysis of stability mechanisms,

and assessment of real risk,

is essential.

Stability is not decreed, it is observed

In single-layer armour layers, field reality always prevails over:

theoretical assumptions,

numerical representations,

and purely documentary validations.

A breakwater is stable not because it is declared compliant,

but because its armour units:

are correctly interlocked,

are firmly supported,

and are free from unfavourable evolution mechanisms.

En conclusion : éviter ces dix erreurs, c’est sécuriser l’ouvrage

The ten errors presented here are common to all single-layer armour systems using artificial concrete units, regardless of the block shape or their origin.

They are not related to the technology itself, nor to the design,

but almost always to:

construction execution,

inspection and control,

and a real understanding of how single-layer armour layers function.

Avoiding them means:

preserving the durability of the structures,

securing investments,

limiting corrective works,

and ensuring the long-term stability of maritime breakwaters.

CLAS has developed its approach specifically to identify, analyse and correct these errors while it is still possible, relying on field experience, recognised best practices, and a rigorous risk-based analysis.

These ten errors are not the result of chance.

They reflect two radically different approaches to the construction of single-layer armour systems.

On the one hand, an execution approach in which placement is treated as a simple positioning operation, where inspections are spaced out or carried out too late, and where excessive reliance is placed on indirect tools, to the detriment of real, direct observation of the structure.

On the other hand, an approach based on a fine understanding of interlocking mechanisms, continuous control of placement, and the immediate analysis of non-conformities while they are still reversible.

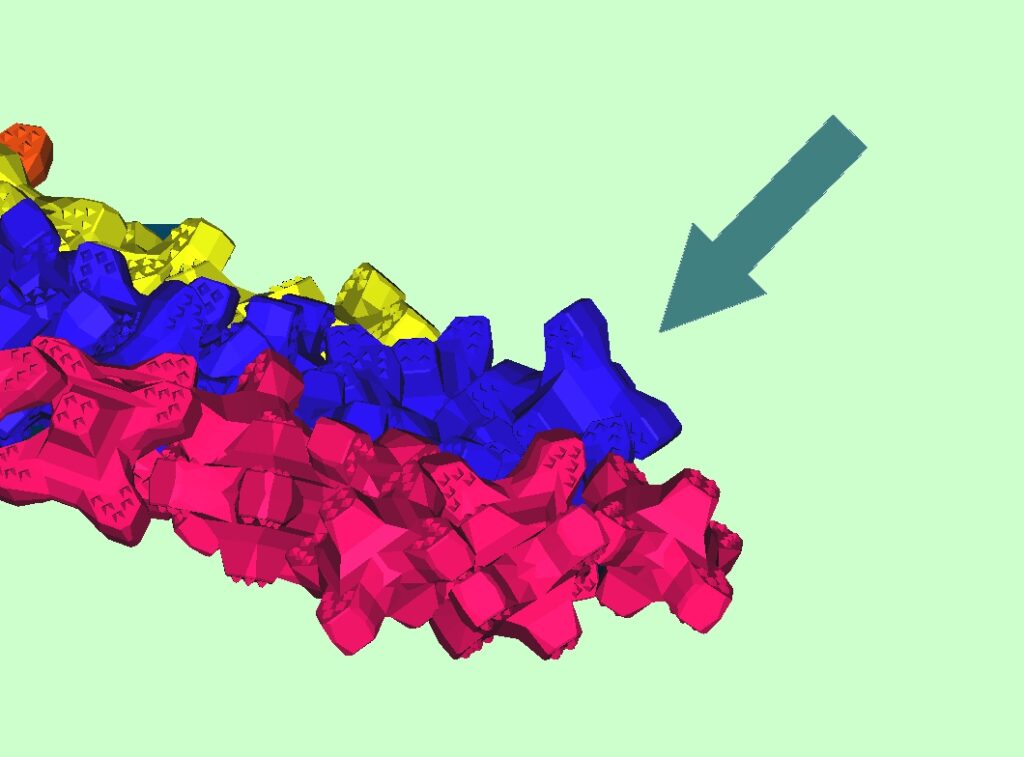

The images below illustrate this difference in concrete terms.

They do not show success or failure linked to a particular technology, but the direct result of the methods applied on site.

Single-layer armour presenting cumulative placement and inspection defects.

Non-conformities not corrected during the construction phase, interlocking defects and late inspections leading to progressive unravelling of the armour layer and to major remedial works.

Single-layer armour compliant with the state of the art – CLAS Method

Block-by-block controlled interlocking, a properly prepared and controlled underlayer, continuous inspections and immediate risk analysis ensuring the stability and long-term durability of the structure.